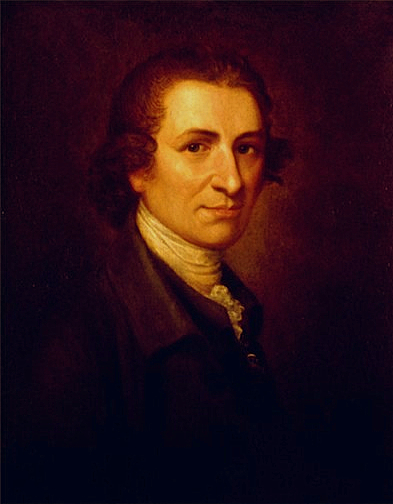

It’s tough to choose a favorite quote by Thomas Paine — American Founder, career revolutionary, and perennial skeptic. Pithy sayings and memorable phrases are Paine’s stock-in-trade, from “We have in it in our power to begin the world over again” to “These are the times that try men’s souls” and even “United States of America” – which first appeared, formally capitalized as our country’s name, in Paine’s American Crisis. In fact, Paine is so quotable that he’s even been credited (or blamed) for a number of things he never said or wrote. The Thomas Paine National Historical Association maintains a handy list of these bogus Paine quotations.

Since I began reading his work in 2009, my personal list of valued (and often memorized) Paine quotations has piled up almost on its own, the way books pile up in odd corners of my bedroom. Most of my favorites are drawn from his deist work The Age of Reason (1794-1795), a rationalist and often satirical critique of the Bible and organized religion. The book is filled with beautiful, compact, often proverb-like turns of phrase: “the word mystery cannot be applied to moral truth, any more than obscurity can be applied to light,” “The word of God is the Creation we behold,” and perhaps most famously: “My own mind is my own church.”

Still, if I had to pick one line of Paine’s that struck me on first reading, and that continues to linger for reasons that I can only partially explain, it would be this:

“ … the glide of the smallest fish, in proportion to its bulk, exceeds us in motion almost beyond comparison, and without weariness …”

Yes, that’s Thomas Paine — also in The Age of Reason — here stepping, however briefly, into the role of nature poet. This passage might seem atypical of his work. It carries none of the rhetorical or political punch of his more famous dictums. There is no humor, no sarcasm, no argument to be clinched. It reads like something pulled from the Tao Te Ching, or perhaps from the work of Paine’s friend, the iconic romantic poet William Blake.

Yet this is the line I always return to in thinking about Paine’s life and works. For me, it expresses not only a love of nature, but a deep sense of kinship with and compassion for other living beings.

It also marks the place where the narrative of my own life intersects with Thomas Paine’s.

In the fall of 2009, I was in one of life’s valleys. Two years out from breast cancer treatment, emotionally and physically exhausted, I had begun to realize that my more-than-ten-year marriage was unraveling. The daily care of my seven-year-old autistic son was making me ever more homebound and isolated, and the clock on my still incomplete Ph.D. dissertation was about to expire.

Somehow, I also found myself absorbed in reading The Age of Reason. I consumed it at first in small bites – a page or two each day. For fiction-writing purposes, I told myself. Background to understand the Enlightenment as a time and place. Fodder for the great historical romance I was going to create.

It wasn’t long, however, before my research became an addiction. I found myself reading Paine for the sheer and sometimes perverse joy of it. I loved following the turns of his arguments. I savored his gift for irony, his keen eye for the illogical and absurd. I was fascinated by the way his writer’s voice could shift on a dime — from biting sarcasm to patient pedagogy to pure lyricism — sometimes in the space of a line or two. Thomas Paine became for me the eccentric but lovable friend who sat each day at my kitchen table, cheering me up with rude jokes about religion – about the Bible, heaven, hell, and the devil – all things that I had been taught to regard as deadly serious during my childhood.

One afternoon, as I was coming to the end of the book, Paine — after a series of bitter arguments with the apostle Paul — abruptly dropped his tone of relentless skepticism. As if reductionist logic had finally exhausted even him, he paused in his argument to simply observe. I followed his gaze — and suddenly there it was:

“Every animal in the creation excels us in something. The winged insects, without mentioning doves or eagles, can pass over more space with greater ease in a few minutes than man can in an hour. The glide of the smallest fish, in proportion to its bulk, exceeds us in motion almost beyond comparison, and without weariness. Even the sluggish snail can ascend from the bottom of a dungeon, where man, by the want of that ability, would perish; and a spider can launch itself from the top, as a playful amusement.”

I was reading aloud, as I sometimes do with very old or very complex works (slowing down and hearing the words often helps me to better understand). At that point, and for no good reason, my eyes teared up. My voice broke. I had no idea why.

It was only later that I learned Paine had written this portion of the book while recovering from nearly a year spent in a French prison during the Reign of Terror. He was fifty-seven years old at the time, and while he managed to escape the guillotine, the stress of the ordeal destroyed his health for the remainder of his life.

Yet Paine continued to write, almost until the day he died, despite chronic physical pain and frequent bouts of deep depression. It isn’t surprising to find that in The Age of Reason, he expresses the wish for “a better body and a more convenient form.” “The personal powers of man,” he laments, “ … are so limited, and his heavy frame so little constructed to extensive enjoyment …” It’s a rare moment of self-disclosure for a writer who most often defines himself through political rhetoric and the parsing of ideology.

As his biographers have noted, Paine tended to hide his private identity behind the assumed public roles of revolutionary and social critic. The historian Gordon Wood calls him America’s “first public intellectual.”

Accordingly, our culture has remembered him as an ideologue first, whether we see him as the rabble-rouser and maker of revolutions, or the scourge of religious creeds and establishment thought. Such caricatures, fostered in Paine’s own time – often by his enemies – go a long way to explain present-day efforts to make Paine over into a rabid nationalist or reduce him to ideological “bomb thrower.” I recently came across one piece on the internet arguing that Donald Trump, by virtue of making outrageous statements and voicing “anti-establishment” sentiments, was some sort of spiritual heir to Thomas Paine. The same sorts of claims have been made about Democratic insurgent candidate Bernie Sanders. Of course, neither Trump nor Sanders, nor any modern politician — could have written anything approaching Paine’s genius – and certainly not his brief and lyrical observation of the tiny fish.

Much of Paine’s writing, and particularly his descriptions of the natural world, do not fit neatly into the persona of either Paine the Patriot or Paine the Infidel. The detail of the fish gliding through the water is but one example.

In reading Paine at length, I find that he is not, in fact, generally a writer of “screeds.” Certainly, he can be caustic. He is often impassioned, with a tendency to get swept up in the drama and occasionally grand language of his own arguments (a trait that I, as a writer, find completely lovable). Paine can hurl insults with the best: his characterization of Edmund Burke as drama queen in Rights of Man is a witty extended metaphor that goes on for paragraphs. Yet undergirding all these writing choices – and that is what they are: strategic choices — something else is at work.

In our own time, when politicians can sneer at concepts like empathy and community, it comes as a revelation to find that Paine’s work concerns itself deeply with those very things. The “smallest fish” in The Age of Reason – a seemingly insignificant and fleeting life – becomes the occasion for wonder, for gratitude, and for a much bigger sense of longing that goes beyond the self – a wish that life could be kinder and “without weariness” for us all.

It is Paine’s constant identification with the smallest and the least – the poor, the distressed, and the exploited – his refusal to hold the suffering of others at a distance, that often makes his work so compelling. Compassion is the strong undercurrent of his major works, even when his words are full of righteous rage. In Common Sense, Paine characterizes England as an unnatural parent, callous toward her children in the colonies. Defending the principles of the French Revolution in Rights of Man, he rebukes his intellectual rival, Edmund Burke, for failing to bestow “one glance of compassion” on the wretched prisoners of the Bastille or the sufferings of the common people of France. “Is this,” he asks of Burke, “the language of a rational man? Is it the language of a heart feeling as it ought to feel for the rights and happiness of the human race?” In the same work, Paine repeatedly calls forth images of individual human beings brutalized in under oppressive regimes, “whether sold into slavery, or tortured out of existence …”

In Paine’s very first pamphlet, The Case of the Officers of Excise, written in 1772, two years before he left England for America, we find moving examples of the writer’s first-hand knowledge of poverty, which in the eighteenth century was everywhere visible. “The rich,” Paine writes, “… may think I have drawn an unnatural portrait; but could they descend to the cold regions of want, the circle of polar poverty, they would find their opinions changing with the climate.”

He also understands that ideology is no cure for suffering:

“He who was never an hungered may argue finely on the subjection of his appetite; and he who never was distressed, may harangue as beautifully on the power of principle. But poverty, like grief, has an incurable deafness, which never hears; the oration loses all its edge; and ‘To be, or not to be’ becomes the only question.”

Throughout The Age of Reason, Paine rages against the cruelties visited upon women, children, and other innocents within the pages of the Bible. There are moments when Paine seems almost beside himself at these horrors committed in the name of god. Indeed, his most telling criticisms of scripture rely not on the parsing of fact and logic (though he gives us plenty of that), but upon the idea that the Bible as narrative – as simple storytelling – is ultimately destructive of human compassion.

“To believe the Bible to be true,” he writes, “we must unbelieve all our belief in the moral justice of god, and to read the Bible without horror, we must undo everything that is tender, sympathizing and benevolent in the heart of man.”

This, for me, is what makes Thomas Paine stand out, as a writer, as a personality – as a human being: his huge and fearless compassion – for suffering children, the poor, the disenfranchised, for the spider and “the smallest fish.” This empathy drives his ideology and breathes life into his words. That feeling is crystalized in the image of the tiny, darting fish. I cannot read Paine’s brief reflection on this least of creatures without also considering the “tender, sympathizing and benevolent” heart that took note of its existence, saw a glimpse of the divine, and raised a pen to share that feeling with readers.

A little more than a century after Paine’s death, freethinker and Civil War Union veteran John Remsberg wrote this of Paine’s works:

“They are full of charity, they glow with patriotism, they are warm with love. Even yet, within their lids methinks I feel the beating of the generous heart of him who penned them….”

It is exactly those qualities of love and generosity that draw me to back Thomas Paine’s writings again and again. It is exactly those qualities that we, as a society, stand in desperate need of now as we consider the future of our nation, as we contemplate the functions of a just, and yes, a compassionate, future world.

Dear Chris,

What a fine start to a wonderful site, full of information that is personal to both Paine and you. I love that combination and am already learning new things about the man and about you. This will be an exciting journey.

Best

Ian

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ian —

Thanks for being the first to comment here. That’s a real honor for me, and I’m glad you’re liking the site. Exploring Paine’s personal significance to me was the thing that finally helped me pull all my ideas together here, so I’m very glad (though not at all surprised) that you picked up on that connection.

As the site grows, I hope to highlight many Paine stories and their tellers — like yourself. Let me know if you ever want to guest-blog!

Thanks for reading, and I hope you’ll stay tuned.

Chris

LikeLike

Paine was never mentioned in our history lessons. Lessons and lessons dedicated to pseudo-heroes like Havel. How lucky I was to find Thomas Paine!

I consider The Age of Reason to be the most beautiful confession of one’s love for God ever written; sincere, respectful, deep, touching the heart and soul. I am a classical Deist, so Thomas Paine is like a propeth and saint in one person for me😉.

Thank You for this blog. Great reading.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome. Most of the time I consider myself an atheist — but Paine’s vision of Deism is indeed compelling. The Age of Reason is special to me because it was how I first “met” Thomas Paine — and because I still find it his most personal work. It’s like a window into his feelings and thought processes. The reader is invited to (re)read the bible with him, “over his shoulder” in a sense, or to converse with Paine across the kitchen table. It’s a very revealing book — and so filled with love for all creation. Thanks for reading!

LikeLike